1. Introduction

Overview

This assessment reviews the impact of the My Gakidh Village (MGV) initiative in Toebisa Gewog, Punakha Dzongkhag (district), Bhutan. Utilizing post-project interviews and desk research, this assessment analyzes the successes and challenges of MGV Punakha and presents recommendations for future MGV projects in other Dzongkhags.

Background of MGV

My Gakidh Village is a joint initiative between Bhutan Youth Development Fund (YDF) and Aide et Action that aims to curb rural-urban youth migration and conserve the environment by increasing livelihood skills and sustainable employment opportunities in rural communities. The project—a first of its kind in Bhutan—targets youth unemployment, rural-urban migration, and associated issues among Bhutanese youth.

Before the project was launched, Bhutan was experiencing South Asia’s highest rate of urban population growth and rural-urban migration.1In 2014, about 50% of Bhutan’s population was under the age of 24.2 Between 2010 and 2020, youth unemployment rate that has been persistently between 7.3 and 15.7%.3 These high rates of youth unemployment and rural-urban migration has resulted in the increase of other issues, such as substance abuse, crime, and violence.4

However, youth who have undergone formal or informal training in Bhutan are 45% less like to be unemployed, indicating that training young people helps reduce youth unemployment.5 Additionally, research shows that government and international investment into rural areas reduces poverty and migration out of necessity.6 This turns migration into a choice, as opposed to a necessity for survival.

1 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), “Human Development Report 2009” (New York, 2009), https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2009.

2 Lham Dorji et al., Crime and Mental Health Issues among Young Bhutanese People (Thimphu, Bhutan: National Statistics Bureau, [Government of Bhutan], 2015).

3 Bhutan, ed., Determinants of Youth Unemployment in Bhutan, CIRD Thematic Research Report Series, no. 2 (Thimphu: National Statistics Bureau, 2020).

4 Lham Dorji et al., Crime and Mental Health Issues among Young Bhutanese People.

5 Bhutan, Determinants of Youth Unemployment in Bhutan.

6 Luc Christiaensen and Yasuyuki Todo, “Poverty Reduction During the Rural–Urban Transformation – The Role of the Missing Middle,” World Development 63 (November 2014): 43–58,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.002; Andrea Cattaneo et al., “Investment in the Rural Economy Reduces Pressure to Migrate Internationally,” World Bank Blogs (blog), 2022,

Recognizing the interconnectedness of the issues faced by Bhutanese youth, MGV was launched in 2014 in Toebisa Gewog, Punakha Dzongkhag by Her Royal Highness Ashi Chimi Yangzom Wangchuck, Vice President of YDF. MGV’s mission is to curb rural-urban youth migration and conserve the environment by increasing livelihood skills and sustainable employment opportunities in rural communities.

Its objectives were to 1) empower at least 50 youth to stay in their village; 2) train 50% of youth to become trainers and change-makers in their community; 3) establish 21 economically self sufficient villages that have alternative economic incentives for environmental and ecological preservation; 4) revive traditional arts, crafts, and trades in the communities.

Since 2014, the MGV project has provided skills development opportunities to between 145-190 youth and has opened an Early Childhood Care and Development (ECCD) Center and School. The skills development opportunities have included:

– Computer literacy courses for young monks

– Community-based ecotourism and homestay management training

– Tea-making and cooperative management training

– Tailoring, art and design, and entrepreneurship training

– Organic farming training

– First aid training

– Workshop on children and youth participation in local governance.

2. Methodology

This study utilized a qualitative approach, employing focus groups and interviews to gather data from various stakeholders involved in MGV. Focus groups were conducted with participants engaged in tea-making cooperatives and local guiding.7 These sessions provided a platform for participants to share their experiences and insights on the impact of the initiative. Additionally, interviews were carried out with key stakeholders, including the Gup and the Governor of Punakha, to contextualize the MGV project within the region’s rural development issues and efforts.

Due to logistical, language, and literacy constraints, the survey that was originally planned to collect quantitative data on income and employment was not used. Instead, relative and nonnumerical information was collected through the focus group discussions. In this manner, participants verbally indicated whether their income had increased due to MGV. These methods allowed for the collection of rich, qualitative insights into the program’s socioeconomic impact while accommodating the constraints of the research setting.

7 Representatives from the homestays, tailoring, and digital skills training were not able to attend the focus group.

3. Key Themes

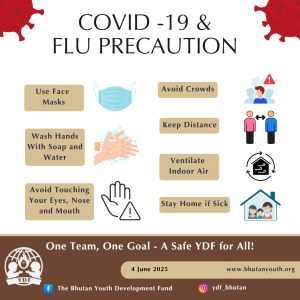

Sustainability of MGV Initiatives: The core issue uncovered by the assessment is the sustainability of project activities without active YDF support. Sustaining the positive impacts of MGV past YDF involvement have proven a challenge for community members in Punakha. This concerns community ownership and leadership, as well as community members’ ability to adapt to changing circumstances (as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic).

Impact of COVID-19: The pandemic significantly impacted local guiding due to the drop in tourism. Tea production was also reportedly impacted by the pandemic, as there was a drop in demand for tea which resulted in the termination of tea production and cooperative activities.

Youth Engagement and Empowerment: Engaging youth is crucial for achieving MGV’s goals of curbing rural-urban migration and addressing associated issues of youth unemployment and substance abuse. Youth engaged in MGV were reported to have seen reduced substance abuse while involved in project activities, highlighting the importance of improving MGV skills development training to sustain long-term youth engagement.

Leveraging Local Governance and Opportunities: The Punakha Dzong is developing a tourism masterplan that will serve as a roadmap to increasing tourism its benefits in Punakha. The Dzong agenda and interest in creating specialty products and marketing the Dzongkhag presents a potential avenue for reviving MGV activities like tea production and local guiding along the Divine Madman Trail. This can enable the revitalization of MGV initiatives without relying on continued support from YDF.

4. Key Findings

Successes

Pre-COVID Economic Empowerment: Participants from teamaking cooperatives and local guides reported that MGV successfully created income generation and economic stability for participants. They also reported that the tailors and homestays have also seen the same benefits.

One local guide shared how MGV gave her confidence. Through learning about her own local history and community, she gained confidence to speak and interact with people outside her community. This confidence gives her the ability to interact with others, including foreigners, to earn her income as a guide.

One tea-maker discussed the stability and freedom she discovered after becoming financially literate. Undergoing tea cooperative management and bookkeeping training, she learned how to manage her own finances. The knowledge and skills she developed gave her financial stability and emotional relief.

Community Development: MGV contributed to community learning and knowledge sharing. Through local guiding trainings, community members learned about the local history of Toebisa Gewog and about their community.

Similarly for the tea-making, participants learned about the local environment and plant species, equipping them with practical knowledge beyond tea. This also connected them with the older generation, as previously this knowledge was limited to elder community members because the younger generation showed no interest in learning about the local plants and their uses. Through MGV, they understood the value of environmental knowledge. The younger generation learned sustainable tea harvesting practices, while the older generation was able to pass down their local environmental knowledge.

Continued Involvement in Teamaking Cooperatives: It appears that despite ceasing teamaking operations due to COVID-19, the two teamaking cooperatives exist.

As a result of MGV, two tea cooperatives have been established, each with five members, totaling 10. While five young women initially received training on teamaking, there are 10 cooperative members. This may be due to the intergenerational learning and knowledge sharing resulted in the involvement of older community members who were not trained by MGV. Alternatively, this may be because the additional five people that were trained on sustainable harvesting practices of raw materials became involved. This retention of participants is higher for teamaking (45.45%) than local guiding (13.89%) and tailoring (20.0%) trainings.

Today, 10 community members continued to be engaged in the teamaking cooperatives. This presents an opportunity in the future to revitalize local tea production.

Homestay and Tailoring Sustainability and Independence: These initiatives continue to see success, demonstrating self-sufficiency and potential for continued growth. While there were no homestay representatives, there were initially two homestays that have been running successfully throughout the years of MGV; however, the Gup (local leader) reported in the meeting that the community has seen the recent addition of a third homestay. This indicates local capability in building and running businesses without YDF oversight and support.

The participants that underwent tailoring training have also reportedly seen sustained success. While they were not in attendance, the Gup shared that three tailors are able to operate a tailoring shop and generate revenue.

Challenges

COVID-19 Impact on Teamaking and Local Guiding: The two tea cooperatives suffered due to the pandemic. The cooperatives ceased activities due to a drop in demand for the product. Since 2020, tea production activities have not resumed.

The pandemic resulted in a significant drop in demand for tourism-related activities, leading to reduced local guiding opportunities. Today, there are five active local guides operating in the

community, and only one is a woman. This is a significant drop in participation from the 36 young people trained on local guiding between 2015 and 2019.8 30 of the participants were female, while the other six were male, revealing that retention of women was significantly low (0.03%) compared to men (66.67%).

Many of the trained local guides may have left the community to pursue other opportunities because of impact of COVID-19 on local guiding opportunities. Another potential reason reported by the focus group is that the young women who underwent training have since married and are no longer working in the formal labor market.

Sustainability Beyond YDF Support: Maintaining momentum and ownership after the withdrawal of external support from YDF poses a significant challenge. Since MGV first launched 10 years ago, it has provided meaningful employment opportunities and income to community members until the pandemic in 2020 and YDF’s phase out. Following 2020, participants and stakeholders have struggled sustaining the program.

The challenge of community ownership is reflected in bridge maintenance for the Divine Madman Trail. The bridges were built for the trail with MGV support to generate more ecotourism activities in the area, increase foot traffic, and provide more opportunities for local guides. After the inauguration of the trail, responsibility for its maintenance was handed off to the community. At the focus group meeting, the local guides reported that the bridges have broken because they were not adequately maintained. The trail is now unusable, limiting the activities and employment opportunities of local guides.

Youth Disengagement: While youth were initially engaged, participation has significantly declined post-COVID, highlighting the need for sustained efforts to retain youth involvement. New youth have not been involved in MGV since its original participants. This highlights the importance of a regenerative programme that continuously impacts new youth in the community, so that current and future youth can benefit.

5. Recommendations

MGV Punakha

Revitalize and Restore Initiatives: The Punakha Dzongkhag’s tourism masterplan presents an opportunity to revitalize teamaking and incentivize the restoration of the Divine Madman Trail. Firstly, reestablishing MGV teamaking production and branding it as a local specialty product in alignment with the Dzongkhag’s agenda to develop a specialty product for the region can address multiple challenges. This can support the tea cooperatives without having to continue relying on YDF.

8 The number of post-training and pre-pandemic local guides is unknown.

Secondly, the Punakha tourism masterplan can help in restoring the Divine Madman Trail and bringing more foot traffic to the community. Aligning the trail with the Dzongkhag’s plan sets up the community to receive an increase in foot traffic, allowing for increased money spent in the community as well as more work opportunities for the local guides and homestays.

MGV Zhemgang

Skills Training: While MGV focused mostly on jobs training and related skills, MGV’s replication in Zhemgang should consider problem solving skills training. By providing such training, the project can set up community members to be self-sufficient. This can help address expected and unexpected challenges that occur.

Hard skills trainings that were conducted in MGV Punakha should be replicated. Bookkeeping and other skills to increase financial literacy can be a huge value to the community and its youth. Because of the teamaking cooperative members’ reflection on the empowerment, lack of stress, and stability it provided, this kind of training can serve to benefit more community members regardless of the type of job training they receive.

Encourage Local Ownership and Initiative: Fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility within the community to sustain initiatives and address challenges independently. Doing this early on, as opposed to during YDF’s exit, will help community members prepare and consider how to manage the initiative’s outcomes long-term. This includes communicating and establishing expectations of YDF’s involvement in MGV.

Develop Strategies for Youth Engagement: Zhemgang has active Young Volunteers in Action (Y-VIA)9and is the focus of Save the Children’s child protection campaign SHIFT. As MGV aims to engage youth and this iteration of MGV has an additional focus of child protection, the active presence of existing initiatives in the region presents opportunities for MGV to facilitate significant and meaningful youth engagement beyond jobs and skills training. The child protection layer can be facilitated and supported by existing resources and networks.

By embedding child protection and youth engagement into MGV and leveraging local networks, this helps develop a regenerative programme that continuously involves, engages, and helps community youth. Building a strong network and support system connected yet external to YDF helps make the community more independent and MGV more sustainable.

6. Conclusions

While the initial impact of MGV Punakha was positive, demonstrating tangible economic and social benefits, sustainability remains a key concern. A focus on community ownership and

9 Y-VIA is a YDF youth network involved in community service across Bhutan. With 5,000 members, it is the largest youth network in Bhutan.

strategic alignment with government initiatives is crucial for the long-term success of MGV in Punakha. As for the next iteration of MGV in Zhemgang, this assessment provides lessons on the importance of building sustainable mechanisms early on and providing both soft and hard skills training.